-

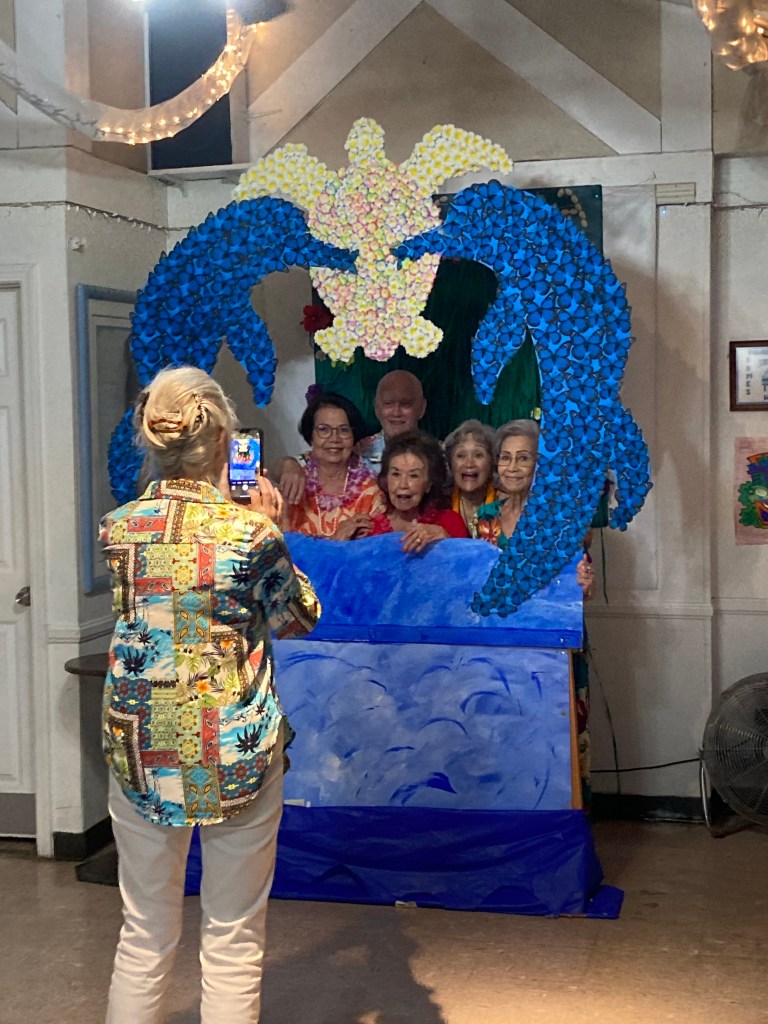

AVIO members at Hawaiian night August 4, 2024 How tens of thousands of Dutch Indonesians ended up in the US: ‘Our children need to know where they come from’

Originally published in TROUW on April 4, 2025

Hawaiian night at Dutch Club Avio in Anaheim, California, on August 4, 2024, is fully sold out. Around the bustling crowd, colorful masks and flower garlands adorn the walls, hung between Delfts Blue tiles, windmills, clogs, tulips and portraits of Beatrix and Claus and Willem-Alexander and Máxima. As always, homemade saté is on the menu, because AVIO (Alle Vermaak Is Ons) is one of the largest and last Dutch Indonesian bastions in the United States.

Although most attendees are well into their golden years, 28-year-old Justin Vitato is having a great time. As the “oudjes” dance to live Indorock, he’s sipping a cold beer at a pineapple-adorned table. “Cheap drinks, good music, nice people, what’s not to like?” he says. Still, Justin doesn’t come here often. He’s here tonight to accompany his oma, Laura Maud Heyman.

Bar ‘T Molentje at Dutch Club AVIO Laura Maud was born in Surabaya in the Dutch East Indies and emigrated to America in the late 1950s with her family, after her grandfather declared he would not “let her go to the land of Al Capone alone.” Her husband Wim Heyman also moved to the U.S. with his Dutch Indonesian family, around the same time.

Laura Maud and Wim were regulars at AVIO’s monthly dance nights and events organized by the social club, which was founded by Dutch immigrants in Southern California in the 1950s. But since Wim passed away in late 2023, Laura Maud has not been back. Too many familiar faces, too many memories. Tonight, her entire family came with her to provide moral support.

Justin even brought a friend, who is very impressed by everything he sees. “We don’t have anything like this in my culture,” he says. As a Mexican-American, Alex knows a lot more about his ancestry than Justin, who, like many young Dutch Indonesians who were raised in the U.S., never learned much about the history or culture of his ancestors. Lately, however, Justin has been trying to dig into his cultural roots more deeply. “That’s why I brought Alex with me tonight,” he says. “To share some of my culture, before it is too late. Who knows if this place will still be around in five years?”

The history Justin is hoping to connect to, is quite literally written on the walls here. Next to bar ‘T Molentje, where Heineken, Bintang beer and Oranjebitter are waiting for thirsty dancers, a large wall is decorated top to bottom with copies of passenger lists, pictures of ships that took many of AVIO’s members from the Netherlands to America, and maps of the places in Indonesia where they were born.

Wall of Fame at Dutch Club AVIO Like most Dutch Indonesians in America, AVIO-members were often able to emigrate with a special visa program that has remained relatively unknown in the Netherlands. Following the Dutch flood of 1953, tens of thousands of refugee visas were made available through the Pastore-Walter Act. But aside from Zeeland farmers impacted by the flood, the Dutch government also encouraged Dutch Indonesians to apply for these visas.

According to a governmental report from 1952, “Eastern” Dutchmen and women would never fully integrate in the Netherlands, setting them up to become a societal burden. The special refugee visa presented the Dutch government with a unique loophole to resolve this fear.

Until then, Dutch Indonesians struggled to obtain American visas, due to strict rules and regulations for immigrants of Asian descent. The Pastore-Walter Act allowed them to circumvent those rules, which the Dutch government was eager to make them aware of.

AVIO (ALLE VERMAAK IS ONS) “America. Where the sun offers an almost limitless display of what you always imagined your new home to be,” begins a documentary produced by the Dutch Emigration Services titled A Place in the Sun , shown to Dutch Indonesian audiences in the Netherlands. And even though the American government complained about the high number of “half-casts” that made use of the Pastore-Walter Act, between 25 to 35 thousand Dutch Indonesians ended up relocating to the United States in the 1950s and 60s.

Most settled in Southern California, where they soon became one of the most successfully integrated immigrant communities. “Many were able to buy a house and send their children off to college within a five year timespan,” says professor Jeroen Dewulf, who teaches Dutch & German Studies at UC Berkeley and researched the plight of Dutch Indonesians in the U.S.. “But,” Dewulf adds, “that success was two-sided.” It also led to the erasure of cultural identity, making Dutch Indonesians one of the most invisible and unknown immigrant groups in America.

For those moved there, the United States offered an opportunity to start with a clean slate: the Dutch East Indies no longer existed, the Netherlands had been left behind. Better to blend in and adapt to the new world, was the leading sentiment. The past was generally left untouched and not spoken about, meaning family histories and cultural knowledge quietly disappeared into the background. Children were raised in English and with American customs. Countless Dutch Indonesians or “Indos” grew up in America, a country where claiming proud ownership of your ancestors’ culture is the norm, without ever learning about their “Indische” culture or history.

Dutch Indonesian author and entrepreneur Tjalie Robinson, born in 1911 as Jan Boon, would have liked to see this unfold differently. He saw America as the one place that could offer Dutch Indonesian culture a unique opportunity to thrive. “People can remain true to themselves in America,” he argued. “Only in Holland do people still foolishly believe in assimilation.”

In the Netherlands, Robinson had founded the Pasar Malam Besar (Tong Tong Fair) and magazine Tong Tong, currently published as Moesson Magazine by his granddaughter, Vivian Boon. In Dutch society, however, Dutch Indonesian culture was consistently proscribed to the margins. Robinson predicted things would be much different in America: “If there was ever a future for Indischen as a group, that future will be born here. Assimilated into oblivion after one generation? Nonsense.”

Tjalie Robinson in San Diego (Photo courtesy of Attinger family archive) When Robinson moved his own family to California in 1963, he immediately launched an English version of his magazine, The American Tong Tong. He also opened De Soos in Pasadena, a community center for gatherings and events with the local Dutch Indonesian community. At local fairs, he presented traditional clothing, Dutch Indonesian dishes and an Indische Hall of Fame to represent their culture.

Yet Robinson’s hopeful American experiment was short-lived. Few of his fellow Dutch Indonesians who’d moved to the U.S. shared his enthusiasm for preserving and promoting their collective culture. In 1968, Robinson remigrated to the Netherlands, bitterly concluding that “our community is one of thirty thousand people with thirty thousand minds, who are each só stubborn and yet só fragile in wanting to go their own way, that neither the group as a whole, nor the individual, truly achieves anything.”

Lately, however, interest in Dutch Indonesian history and culture amongst the younger generations is growing. It is challenging for them to find information, however. Historical sources are mostly in Dutch or Indonesian and the colonial world their ancestors were born into no longer exists. Non-profit organization The Indo Project has made historical resources, information and interviews accessible in English on their website since 2009, but many young people are also looking for a more intrinsic connection to the Dutch Indonesian community and culture. This is where organizations like SoCal Indo come in.

SoCal Indo group photo (Michael Passage middle front) “People would constantly approach me in Spanish,” says 57-year-old Micheal Passage, who emigrated to Los Angeles in 2002. Like many Dutch Indonesians in America, strangers often mistook him for Latino. “That’s why I started wearing a SoCal Indo T-shirt, initially as a kind of joke,” he says.

SoCal Indo stands for Southern Californian Indo. Passage was raised in Belgium, after his parents moved there from Indonesia in the 1960s. When he moved to the U.S., he’d expected Americans to lack knowledge about Dutch Indonesian history. But it was mostly local Indos who’d approach him asking all kinds of questions when they saw his T-shirt.

In 2012, the T-shirt turned into a Facebook group and a YouTube series titled Meet The SoCal Indos, for which Passage interviewed young and older “SoCal Indos” in his own unique style. With the motto Awareness, Unity, Support, Passage hoped to turn SoCal Indo into a platform that could inform and unite the local Indo community across generations. He wanted to involve the AVIO in this as well.

“Everyone knows AVIO here,” Passage says. “Everybody’s oma and opa went there. It’s part of their lives, their immigration story.” Since young Indos rarely attended AVIO events—”They’re not that into Indorock”—Passage began to organize his own events, with modern music and Indische dishes. But while the younger generation flocked to these events, older generations tended to stay away, much to Passages chagrin. The reason for this can’t be distilled down to a mere difference in music taste. It is likely also due to differing views on Dutch Indonesian history.

SoCal Indo Kumpulan Passage likes to organize events at the Indonesian Consulate, which can be off-putting to the older generation. “‘Why would I go there, when they kicked us out of the country,’ is the kind of thing people tell me,” Passage says.

Personally, he views things very differently. “Soekarno gave people a choice,” Passage argues. “You’d either adapted to the new Republic, or you’d leave for the Netherlands.” Family members of his who remained in Indonesia did very well there. Passage even lived in Indonesia himself for several years. Including the local Indonesian community in his events therefore makes sense to him.

But for older Dutch Indonesians, the relationship to Indonesia feels more complicated and tends to touch on deeply seated sensitivities. Multiple AVIO-members personally witnessed or experienced extremities of Indonesian violence after World War II. Those experiences aren’t discussed much, but they do keep some people from, for example, attending events at the Indonesian consulate.

Meanwhile, shared trauma does play a role in the emergence of Dutch Indonesian enclaves such as AVIO, says professor Jeroen Dewulf. Many Dutch Indonesians who relocated to America had lived through multiple disruptive and sometimes traumatic events: World War II, the Indonesian war for independence, two Trans-Atlantic emigrations. “Only someone who’d gone through something similar could really understand them,” Dewulf explains. This informed a special sense of solidarity amongst Dutch Indonesian immigrants, Dewulf explains, “much more than amongst Dutch immigrants who’d emigrated to America.”

That’s part of the reason why the first generation kept coming to the AVIO. Not necessarily to keep Dutch Indonesian culture alive in America, but to enjoy the present and forget the past, amongst others who intimately understood how hard the latter could be. Some eventually did find the trust and courage in these shared spaces to talk about their traumatic experiences. “It’s absolutely horrifying what these people have had to live through,” says Henny Piening, one of the few Dutch members who remained active in the AVIO. “I never learned anything about that in the Netherlands.”

Photo booth at AVIO’s Hawaiian night But AVIO primarily offered “gezelligheid” and music, family and friends, birthdays and anniversaries: a place to create positive memories in a new country and to combat loneliness and isolation. That’s how AVIO became a lifeline of sorts for an aging generation, the future of which is now uncertain.

“You should come here more often, the club needs more young people now!” 87-year-old John von Bargen tells Justin Vitato as he comes to say goodbye. “It’s dying, the AVIO,” Von Bargen explains. “There’s less and less and less people.” As of yet, no one has stepped up to continue with what AVIO has built, and it’s unclear how long it will remain.

Losing AVIO wouldn’t just be a huge loss to his own generation, Von Bargen fears, but for the younger generations as well: “Our children need to know where they come from. They should not become fully Americanized.”

Still, passing the baton has proven challenging. Since becoming a non-profit organization in 2024, SoCal Indo supports charities in Indonesia, for which it has collaborated with AVIO on occasion. Last year, a benefit concert and a family event for the Harley Davidson Indonesia club took place at the AVIO venue. But early 2025, the future of such collaborations suddenly turned shaky.

Michael Passage wanted to organize another benefit concert for victims of the LA fires at AVIO. But according to AVIO’s board members, the event couldn’t take place at their venue. Seething, Michael posted an angry and heavy-worded message to Facebook. The next day, he removed the message and posted an apology video to Facebook, explaining he’d let his emotions get the best of him.

Sign outside AVIO in Anaheim, CA Several young Dutch Indonesians responded to the video, stating that they don’t feel welcome at AVIO, while others argued that the older generation deserves more respect for what they’ve built. Ultimately, everything was smoothed over and the concert took place at AVIO after all, but tensions like these are hard to fully erase.

According to Passage, Indos tend to be stubborn and easily offended, himself included: “There’s always some quarreling between groups.” Still, Passage has a more positive outlook on the future than Tjalie Robinson did, when he made a similar assessment about his peers in 1968. “We just need to keep the fire burning, I don’t care how,” Passage says, although he does hope young and old can come together and find common ground more often. “In the end, we are stronger together.”

This publication was made possible with support from Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten (www.fondsbjp.nl)

* With special thanks to and in loving memory of Petra Pijpaert Hameeteman.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.